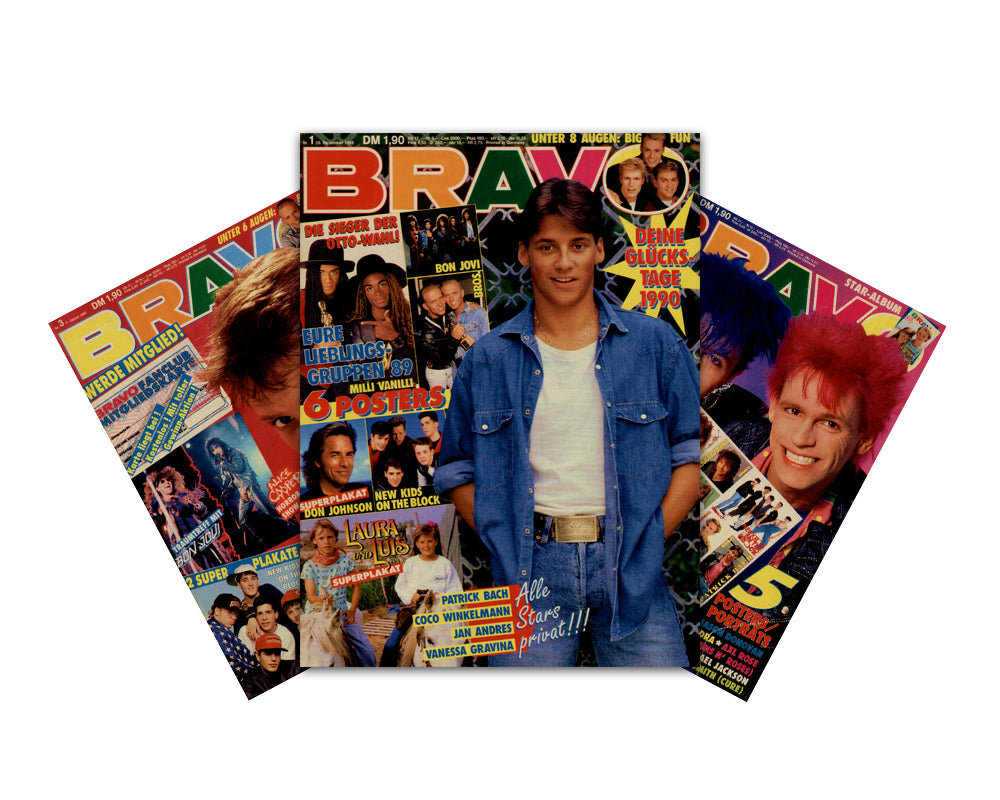

If you purchase 3 individual issues, you can take one additional issue free .

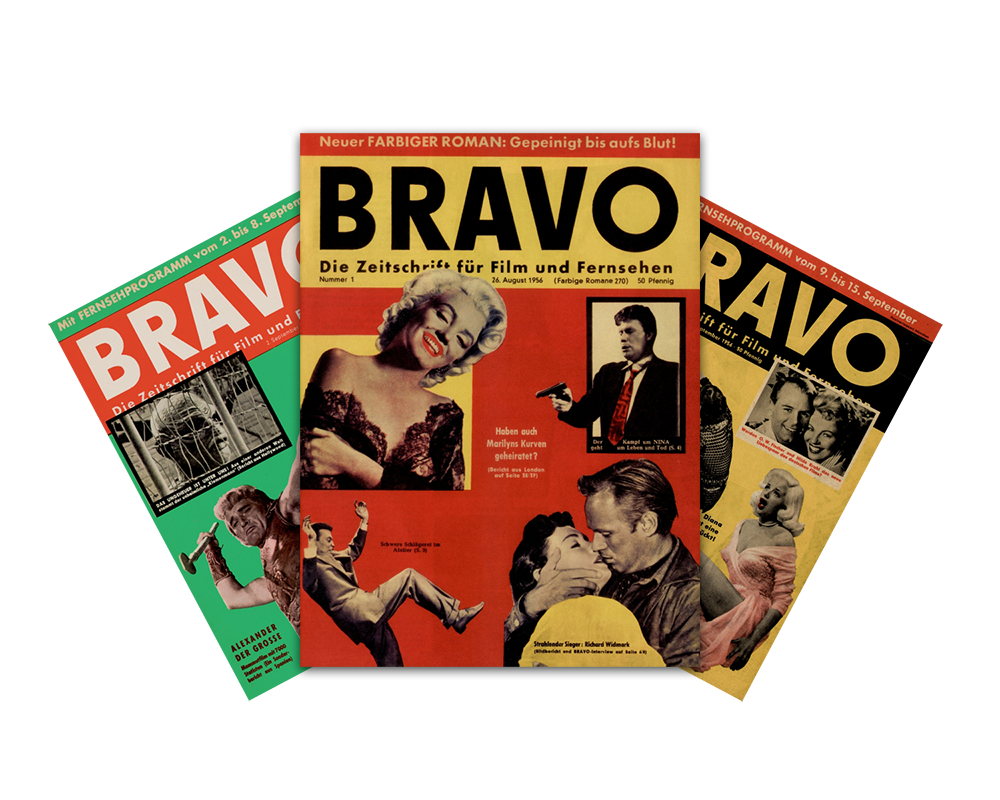

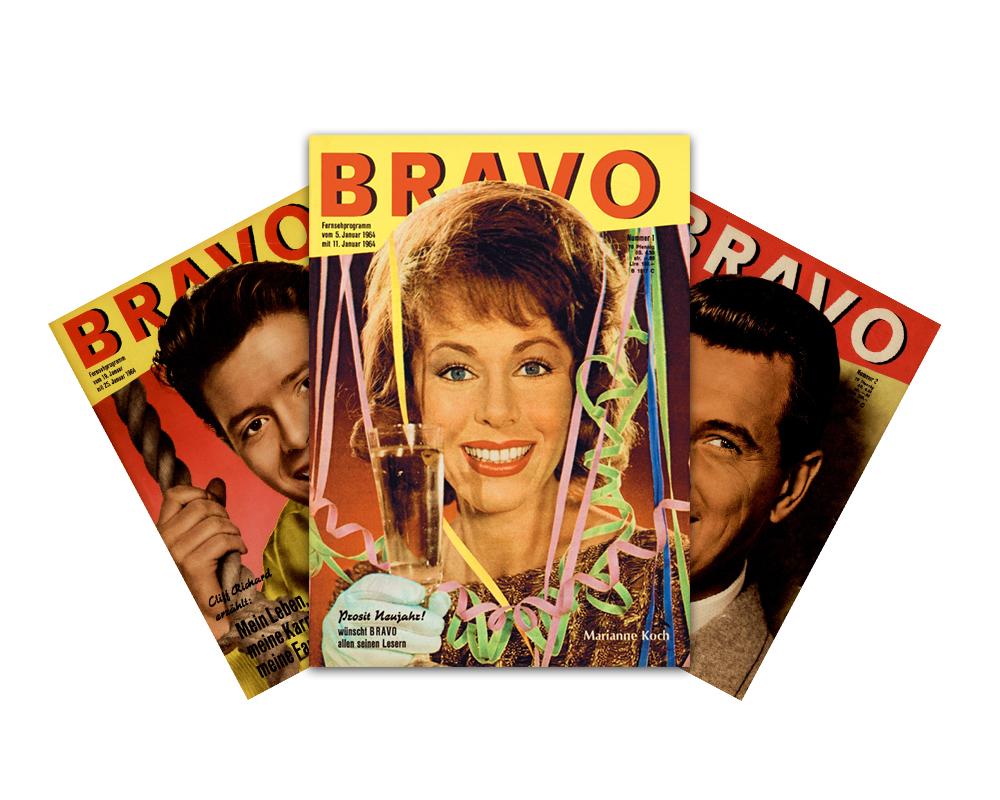

The first BRAVO

When the first, forty-page issue of BRAVO – The Magazine for Film and Television – hit newsstands eleven years after its surrender, Germany was still far from recovering from the consequences of World War II. In every city, alongside hastily rebuilt houses, one could see ruined lots with bomb craters and random vegetation, which children often used as playgrounds. The scars of the Great War were visible everywhere: bullet holes, piles of rubble, ruins, gaping wounds in rows of houses, commandos were constantly deployed to defuse unexploded bombs, and disabled veterans were a common sight on the streets.

It wasn't until 1955 that a particularly moving chapter in post-war history came to a belated end with the "Homecoming of the Ten Thousand." During a trip to Moscow, Chancellor Adenauer secured the release of the last 30,000 soldiers and civilians held as Russian prisoners of war. This grim past contrasted with a bright future. Care packages, the Marshall Plan, and currency reform were followed by the much-praised economic miracle. The Germans embraced the motto of their Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard, "Prosperity for All" – only too gladly, and the first successes quickly became apparent. The federal government imposed a housing control system to defuse the dramatic situation in the cities, and between 1949 and 1956, around two million social housing units were completed at a pace no one had thought possible. The way was also paved for subsidies for the construction of private homes. On Christmas Day 1952, the first German television station went on air with two hours of programming in the evening. In 1955, the 1,000,000th Beetle rolled off the assembly line in Wolfsburg, and employees and dignitaries crowded into the factory hall to celebrate this success. While there were still over two million unemployed at the beginning of the 1950s, by 1955, the first guest workers were being recruited. Full employment was not a dream, but a reality – even on Saturdays, which were still a completely normal workday. It wasn't until 1956 that the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) launched its striking campaign for the 40-hour workweek: "Saturdays belong to me!"

In their limited free time, people drove to the countryside. In the 1950s, the streets were dominated by the famous Wolfsburg Beetle and the sleek Karmann-Ghia designed by Italian designer Luigi Segre, as well as often-mocked vehicles such as the Messerschmitt Kabinenroller, the Lloyd LP 300 (“He who doesn't fear death drives a Lloyd!”), the BMW Isetta, and the Goggomobil. Those who, for love, weren't too fussy about money could buy a Borgward Isabella for the hefty price of 7,000 DM or even drive an Opel Rekord.

With a younger target audience in mind, BRAVO focused on mopeds, scooters, and mokicks. Heinkel, Vespa, Kreidler, Zündapp, Lambretta—the manufacturers' imaginations seem to know no bounds. This is also demonstrated by numerous double-page spreads in BRAVO, which focus on the wide range of products available on the market.

Mobility was one of the major themes of the 1950s. This applied both to personal mobility, in the form of a motorized two-wheeler or car, and to general mobility, meaning the increasing travel activities of Germans. Lufthansa was founded in 1954. Just one year later, the airline established scheduled service to South America and the Far East and continually expanded its route network. Dream jobs of the time included—not surprisingly—pilot and stewardess, even though the flight from Düsseldorf to New York still took 13 hours.

However, due to the astronomical prices, air travel is more often reserved for business people. The majority of people travel within Europe by train, while for overseas travel, by sea. The first tourism companies, such as Touropa, advertised their "Holiday Express" with the slogan "The elegant holiday train with a reclining bed for every guest"; and "Neckermann makes it possible" became a popular saying at the time. But here, too, travel was not something to be taken for granted as it is today, but rather an adventure. Most Germans at that time vacationed in the surrounding countryside or on their balconies. Trips to the North Sea and Baltic Sea, excursions to the low mountain ranges – vacations far away were unaffordable for many. Organizations whose names still recall the state-organized vacation activities during the Nazi era helped them. Thanks to the evacuation of the country, the children were out of the house, and the mothers were traveling with the Müttergenesungswerk (Mothers' Recovery Fund). Nevertheless, by 1956, around five million Germans were already registered as heading south. Entire convoys of beetles roll over the Alps to Italy, which becomes the epitome of a carefree sun holiday. The effects are also unmistakable on a musical level: 'Capri Fischer', 'O Mia Bella Napoli', and 'Ciao Ciao Bambina' are the resounding tunes that, together with the 'Saltwater' songs of the singing sailor Freddy Quinn, further intensify the wanderlust.

In general, after years of propaganda-driven paternalism and war-related deprivation, the motto was: entertainment, preferably light fare. While Germany toiled, the radio blared incessantly, triumphing at that time over the few television sets (only two percent of all households owned this technological advancement). And "The Light Breeze from the Southwest," as one of the radio programs was called, wafted primarily German-language songs and hits into the living room. The only foreign-language song contributed to the hits of 1956 was a 34-year-old American actress of German descent. Born Doris von Kappelhoff on April 3, 1924, in Cincinnati, Ohio, she followed the advice of a nightclub owner in the late 1930s and adopted the surname "Day." With considerable success. One of her most popular songs became "Day after Day." But the most popular song is "Qué sérà (Whatever Will Be, Will Be)", a hit from the legendary Hitchcock classic "The Man Who Knew Too Much".

Otherwise, a multitude of German songs dominate the airwaves: songs by Freddy Quinn and Fred Bertelmann, Ralf Bendix, Rudi Schuricke, the Eilemann Trio, and Caterina Valente, an exceptional figure in both German and international showbiz. The talented scion of an Italian family of performers (born on January 14, 1931 in Paris) excels not only in her career as an actress, but also as a singer and entertainer. She changes languages (she sings in a total of twelve different languages) as frequently as she changes the name of her group: Club Indonesia, Club Italia, Club Argentina, Club Manhattan, Club Honolulu, and Catrin's Madions Club are just a few of the compilations she has appeared in. In the 1950s, she enchanted audiences with catchy tunes like "Ganz Paris träumt von der Liebe," which sold a sensational 500,000 copies, and sang numerous duets with her brother Silvio Francesco and Peter Alexander.

The Austrian singer and actor laid the foundation for his unique career in the 1950s, a career in which films, often with music and dance interludes, played a significant role. Going to the movies was one of the most popular pastimes of the post-war generation. And here, too, light fare was preferred. The average consumer especially loves Heimatfilme (homeland films), which can probably be considered the only truly German film genre. The titles promise plenty of nature and emotion: "Where the Wildbach Rushes" and the Heath Grows Green, that's where "Schwarzwaldmädel" (Black Forest Girl) and "Der Förster vom Silberwald" (The Forester of the Silver Forest) are at home. The undisputed stars of this new genre are Sonja Ziemann and Rudolf Prack. These sentimental films perfectly portray the ideal world longed for in the postwar years: "The Heimatfilm was a mirror of the social trends of the 1950s. It contrasted the struggles and worries of everyday life with idyllic images of a different life. It showed a perfect, intact natural world. People didn't want to see war ruins in the cinema either. The Heimatfilm was a balm for chafed souls," write Rüdiger Dingemann and Renate Lüdde in their book "Germany in the 1950s. Those were the days!"

It's important to protect these chafed souls, and so it's little wonder that in 1952 a film like "The Sinner" caused a real scandal. The young Hildegard Knef was briefly seen naked in one scene. It wasn't just the naked facts, however, but rather the themes of prostitution, euthanasia, and suicide that stirred emotions. Knef plays Martina, who loves the elderly, seriously ill painter Alexander. To enable him to have an expensive operation, she works as a prostitute for him. But the cure never comes, and Martina, unable to bear to see her lover suffer, kills him first and then herself. Strong stuff for a society seeking to distract itself. Apart from a few ambitious films such as Bernhard Wicki's "The Bridge," the Carl Zuckmayr adaptation "The Devil's General" (about the suicide of Air Force Colonel Udet), or the crime documentary drama "The Girl Rosemarie," which deals with the scandal surrounding the murder of high-class prostitute Rosemarie Nitribitt, the German enjoys screen fairytales such as the "Sissi" trilogy, which helped the young Romy Schneider achieve world fame.

In 1956, however, other tones also mingled with this ideal world. Politically, the debate about militarism dominated the headlines: Adenauer pushed through the Conscription Act against the resistance of numerous interest groups, which was passed by the Bundestag on June 9. On April 1 of the following year, twelve years after the fall of the "Thousand Year Reich," the first conscripts returned to German barracks. And on October 25, Hitler was officially declared dead by the Berchtesgaden District Court. History had marched over the "greatest military commander of all time" with seven-league boots.

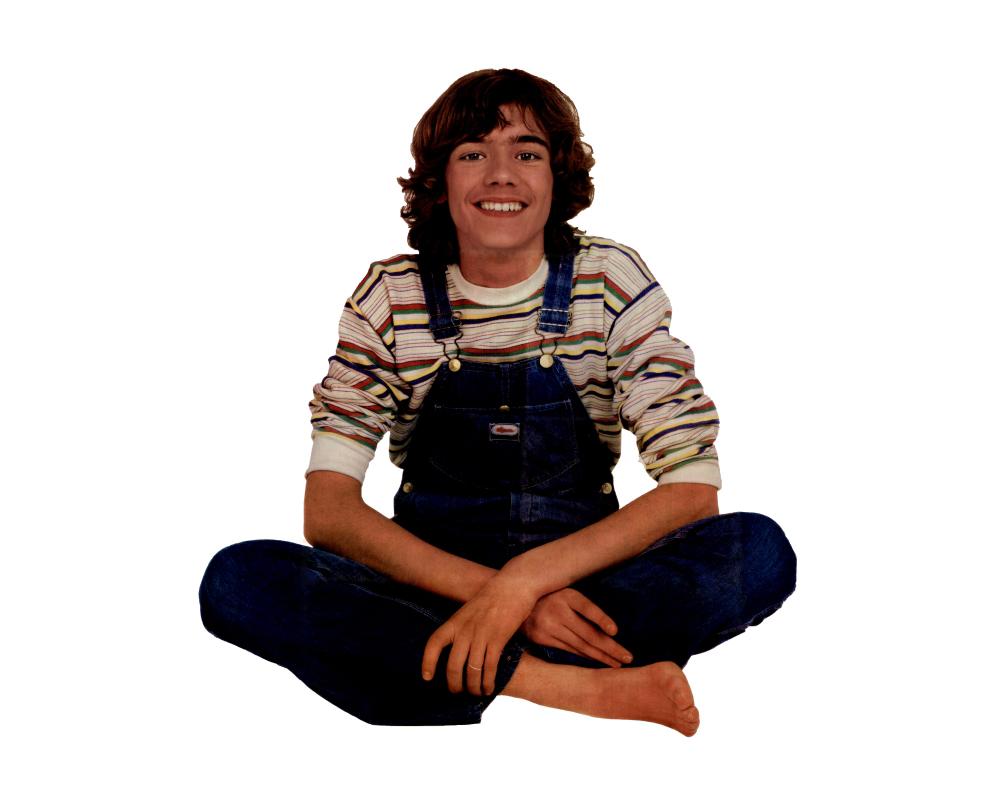

The German James Dean is called Horst Buchholz

In film, radio, and television, a wave from America swept over Germany during this period, attracting young people in particular. While the more sophisticated generation watched "Sissi," they stormed into "Giants," the last film with James Dean. The previous year, the Porsche fan had died in a car accident. German filmmakers reacted and, to the annoyance of strict moral guardians, copied the American cinematic rebels whom the young people emulated. The German James Dean was Horst Buchholz: In 1956, Hotte played the 19-year-old youth gang leader Freddy in "Die Halbstarken," directed by Georg Tressler and alongside young star Karin Baal. The film—its poster boasted the enticing slogan "hard... realistic... contemporary"—sparked nationwide debate and, of course, was also extensively reviewed in BRAVO. The first issue also contains a curious report related to the controversial film: Under the headline "Revenge of the Teenagers," it is reported that such teenagers ambushed Will Tremper, the screenwriter of the "Teenager" film, first beating him up and then sending him acetic acid clay two days later.

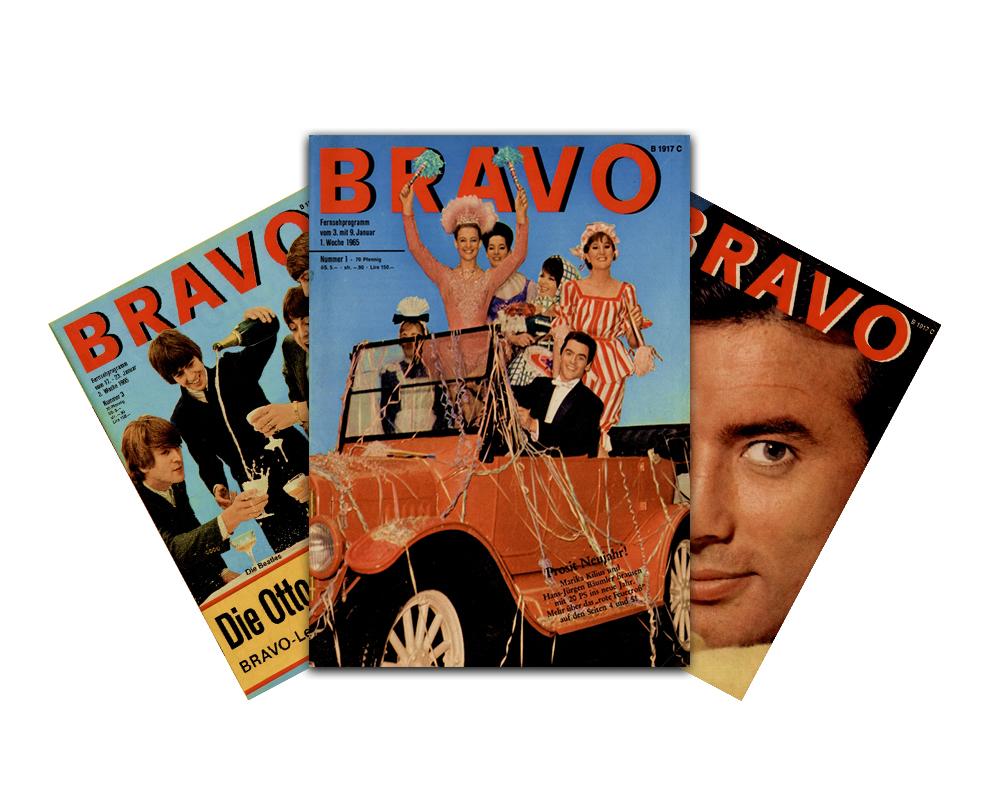

Besides Hotte Buchholz, it was primarily Hollywood stars who were honored in BRAVO at that time. The cover of the first issue was dominated by a smiling Marilyn Monroe and Richard Widmark. And that was no coincidence. Cultural researcher Kaspar Maase sees the image of the cool, casual American as the antithesis of the still

Germans influenced by militarism. In his essay "Medium of Youthful Emancipation: BRAVO in the Fifties," he concludes that the teen magazine decisively shaped the self-image of German youth and "certainly contributed significantly to ending the clawing veneration of German militarism." However, BRAVO's contribution to the spread of the second wave, which swept across the pond, was rather slow. Like the parents' generation, the magazine initially kept its distance from rock 'n' roll. It wasn't until its 15th issue that the magazine published the first two-page portrait of Elvis Aaron Presley . The "hip-wiggler" was also the first full-time non-actor to grace the cover of BRAVO: On December 30, 1956, his portrait beamed out to readers. Nevertheless, the editors weren't entirely comfortable with the new musical genre. Rock 'n' rollers are called "noisemakers" and equated with the teenagers who haunt the nightmares of morality police. But it soon becomes clear that this musical genre can no longer be stopped. This music, this kind of film, the entire wave of this new youth culture, which BRAVO catered to with its magazines, would bury everything traditional, break with old customs and traditions, and thus threaten the adult world.

Rock 'n' roll was the soundtrack of a new attitude to life, freed from the rules of the old ways: sensuality and sex instead of discipline and order. Mobility instead of "standing still," wanderlust instead of "staying here," and twist dancing instead of push-ups according to the German gymnast Jahn.

Elvis Presley - the ambassador of bad taste

The reaction was immediate: The new King of Rock 'n' Roll, who electrified his young fans with his hip swing ("The Pelvis"), was vilified by frightened moral guardians as "musical scum" or "ambassador of bad taste." Bravo, at least, has since recognized the significance of the man who, along with James Dean, would become the preeminent youth idol. Long after his death, indeed, to this day, the magazine continues to report on the man from Tupelo, Mississippi, who ushered in a new era in pop music. In America, teenagers have long been obsessed with Elvis merchandise. The hottest thing is a lipstick with Elvis's autograph on the tube. The color: "Hound Dog Orange," of course.

What else happened in 1956: A major box office hit of the year was "Upstairs," starring Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly. Afterward, the actress with Irish roots became part of the upper class herself, as she married Prince Rainier III of Monaco as Grace Patricia that same year and secured Monaco's independence from France with the birth of the heir to the throne, Caroline. In Stockholm, a horse became legendary: the mare Halla carried Hans-Günther Winkler, who was handicapped by a torn muscle, to Olympic gold in show jumping.